Fools Mission is in the exploration stage of developing a new program. For now, we’re calling it a Healthy Relationships Seminar. The proposed seminar would be a hybrid between a covenanted support group and a lecture format, and would create space for participants to explore interactively all aspects of human relationship, including couples, families, and the workplace. The fools in our community have requested programs like this, and it’s not easy to deliver one that fulfills our mission. The challenge for Fools Mission is to recruit co-leaders who represent both native and immigrant cultures. Ideally, we’ll have established citizens in the room along with culturally competent Spanish speakers, so that representatives from each culture can hear one another’s stories in both languages. Prompt translation will be essential. So will maintaining an atmosphere of confidentiality and respect.

To strike a balance between U. S. and Latin American culture, a co-leader called a Servidor—loosely translated from Spanish as “one who has embraced a life of service”—would play a role that is part facilitator and part presenter. After speaking about a topic for a few minutes, the Servidor turns over the discussion to each participant in turn, eliciting feedback about what was just said. The idea is to provide enough structure and leadership to create a space of listening and respect, and enough interactive participation to allow the wisdom and support of the group to emerge.

The opportunity for understanding and enrichment is as real as the risk of misunderstanding. We have to anticipate encountering “hot button” topics on which people don’t agree. We’re willing to take some risks, and they’re real enough to warrant our attention. All therapy is culturally conditioned, and has to be culturally appropriate. As psychiatrist and author E. Fuller Torrey said, “A psychiatrist who tells an illiterate African that his phobia is related to a fear of failure and a witchdoctor who tells an American tourist that his phobia is related to possession by an ancestral spirit will be met by equally blank stares.”

The potential rewards are also palpable—psychiatrists cite the Principle of Rumpelstiltskin, which states that the capacity to heal has a strong relationship with the capacity to find a name for our pain. At Fools Mission , we’re often confronted with naming what keeps us separate—only to experience firsthand civilization’s “normalcy” of violence, fear, prejudice, and racism. Our quest for multicultural experiences that build community across socioeconomic class is our antidote to the nation’s eroding capacity for empathy. We favor building friendship and community over relying on untested assumptions.

An anti-therapeutic conversation with a therapist

So I approached some therapist friends of mine in search of a co-leader, and came up with a story that demonstrates first hand why Fools Mission is necessary. The friend I approached taught me some important lessons about how helpful the Way of the Fool can be as a lens for reflection, understanding, and spiritual growth. My friend not only has a PhD, but 14 years of experience with marriage and family counseling. In an email earlier in the week, he had already made it clear that his time was “so very limited” because of his “work and volunteer time.” He said that his cause was “my passion and I have no interest in other community opportunities.”

I began the interview with what I hoped was an open-ended appeal to interpret my request for help any way he chose, whether that be participation, consulting, or advice. While he heard the first option, it became clear that he stopped listening before hearing the other two. The tone and body language of his response—“I thought I made myself clear when I said…”—felt unnecessarily defensive and patronizing to me. But the fool in me realized that to avoid transference, burnout, and other pitfalls that beset practitioners, counselors have to maintain strict professional boundaries. I felt that I should accept that we got off on the wrong foot and try to keep the conversation going.

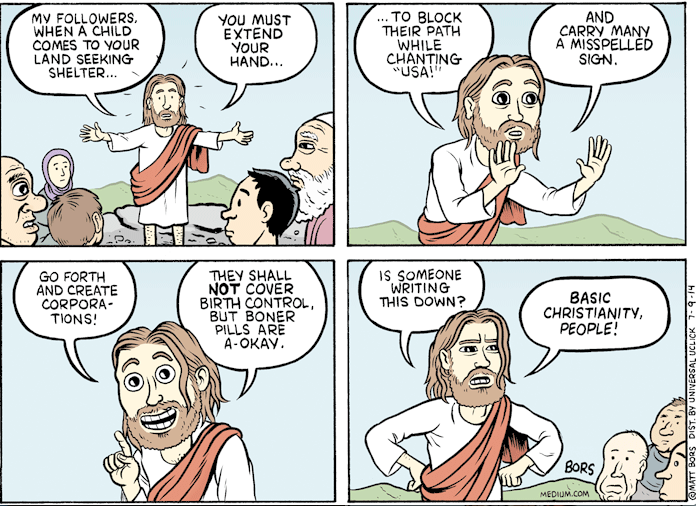

Things got worse from there. He lectured me for five minutes before I was able to say a word about our mission. In response, he expanded his passion for his cause to include reasons why his clients are worthy of his attention and undocumented immigrants are not. I feebly responded that we don’t spend much time separating the worthy from the unworthy, while he emphatically asserted that he did.

Things got worse from there. He lectured me for five minutes before I was able to say a word about our mission. In response, he expanded his passion for his cause to include reasons why his clients are worthy of his attention and undocumented immigrants are not. I feebly responded that we don’t spend much time separating the worthy from the unworthy, while he emphatically asserted that he did.

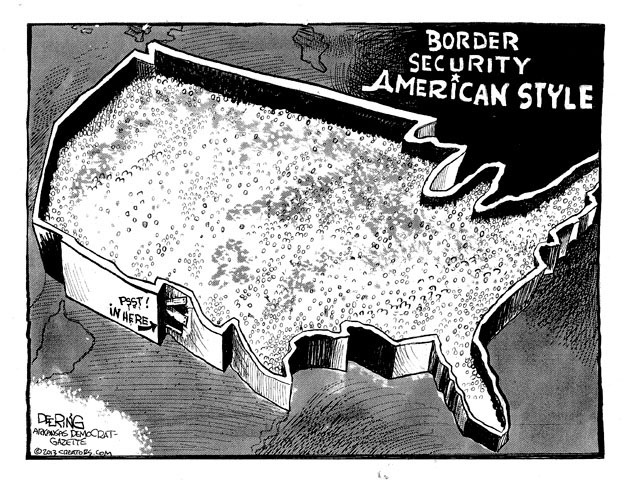

He began to instruct me about how his grandparents were Irish immigrants—but never asked questions about my own ancestors (Irish immigrants). He spoke about how his grandparents became citizens lawfully by getting in line, with no apparent knowledge of the Byzantine process and 20-year waiting line in store for most people under the system that we have today. He had no recognizable grasp of the role of race in the angry, polarized attitudes that we see today. And though he was able to acknowledge that undocumented immigrants were human beings, it was clear to him that the law should determine the fate of the eleven million undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

Interrupting the barrage of patronization and judgment, I was persistent enough to ask him whether he wanted to hear about our proposed program. When I described it, he went into lecture mode again—explaining that he “studied for 24 years for a reason,” and that the state strictly regulates any activity with pretensions to support or counseling. He referred to the history of EST (Erhard Seminars Training) in California, and how the state passed laws requiring that licensed professionals be present at all sessions. Not once was he able to acknowledge that I was trying to recruit volunteers with professional experience by asking him for help. He added that free counseling services are available in San Mateo County, and that you can locate them with a simple Google search.

If I felt patronized before, I was also feeling condescended to by now. But the conversation was helping me to realize that my own commitment to the Way of the Fool was kicking in with newfound capacity for compassion. First, I recognized that my friend’s story of himself and the world is shared by many, and that harsh judgments from me about his anti-caregiver stance and selective compassion would serve no useful purpose. My emerging ability to detect the presence of warrior consciousness and traditional, rules-bound consciousness in his thought process reminded me that if I were born with his abilities and lived his life, I would probably say and do similar things. I was able to feel compassion for the role of oppressive systems in the formation of his worldview, and recognize how his lack of empathy and poor listening skills probably undermine his counseling practice every day. What a hard thing it would be to walk around in his stream of consciousness! Reminded of the inherent justice embedded in the universe, I began to feel sad for him.

If I felt patronized before, I was also feeling condescended to by now. But the conversation was helping me to realize that my own commitment to the Way of the Fool was kicking in with newfound capacity for compassion. First, I recognized that my friend’s story of himself and the world is shared by many, and that harsh judgments from me about his anti-caregiver stance and selective compassion would serve no useful purpose. My emerging ability to detect the presence of warrior consciousness and traditional, rules-bound consciousness in his thought process reminded me that if I were born with his abilities and lived his life, I would probably say and do similar things. I was able to feel compassion for the role of oppressive systems in the formation of his worldview, and recognize how his lack of empathy and poor listening skills probably undermine his counseling practice every day. What a hard thing it would be to walk around in his stream of consciousness! Reminded of the inherent justice embedded in the universe, I began to feel sad for him.

Trust me, I struggle with the Way of the Fool all the time. I can revert to tribal, warrior, or rules-bound consciousness in a heartbeat. I wasn’t born without a brain stem. But I found myself taking encouragement from this difficult conversation instead of becoming demoralized, angry, or defensive. It felt like a new plateau in my own journey as a fool.

Because he had stopped listening before we began, I realized that any attempt to debate immigration or multiculturalism would miss the mark. George Lakoff’s lessons about how “facts bounce off frames of reference” helped me to restrain the urge to wrestle each point to the ground. I could have told him that “the law”—in the form of NAFTA—created millions of new undocumented Mexican immigrants by permitting heavily-subsidized US corn and other Agribusiness products to compete with small Mexican farmers. I could have explained in excruciating detail how laws written on our behalf by fleets of Agribusiness lobbyists drove millions of impoverished farmers off their ancestral lands and into destitution. I could have talked about how NAFTA’s service-sector rules allowed big firms like Wall-Mart to enter the Mexican market and eliminate 28,000 small and medium-sized Mexican businesses.

I didn’t say anything about how schizophrenic the American public can be about undocumented immigrants. (Before you chastize me for misusing a professional term, I mean schizophrenic in the metaphorical sense.) I was silent about the extent to which our way of life depends on access to their cheap labor. “We want to send you back to Mexico—but first, could you please bring me a beer and finish cleaning the house?”

I might have summoned up the patience to explain how—post-NAFTA—eight million desperate people crossed the border in search of a way to feed their children. I might have raised other obvious questions. Without the intervention of basic human decency, how can more legal double-binds and Faustian bargains resolve decades-old layers of conflicting immigration law? Would it have helped to ask him to think about what he would have done if his own children were starving? If his own deportation tore a beloved parent and breadwinner away from his kids? If his own family was being threatened by drug lords?

I might have summoned up the patience to explain how—post-NAFTA—eight million desperate people crossed the border in search of a way to feed their children. I might have raised other obvious questions. Without the intervention of basic human decency, how can more legal double-binds and Faustian bargains resolve decades-old layers of conflicting immigration law? Would it have helped to ask him to think about what he would have done if his own children were starving? If his own deportation tore a beloved parent and breadwinner away from his kids? If his own family was being threatened by drug lords?

Instead of offering arguments, I thought it best to thank him for helping us reach an understanding that we wouldn’t be working together. The way he jumped at that notion with such enthusiasm, patronizingly reiterating how “he thought he’d been clear,” convinced me that he hadn’t heard much of what I had said. I think psychology professionals call it projection. I’m guessing that when our conversation was over, he still didn’t realize that when I said “working together,” I also meant consulting and advice.

I’m a happier person today for having approached my friend with our proposal, whether we eventually implement the new program or not. Now I can see more clearly how our eternal tendency to make distinctions and invoke boundaries makes it necessary for someone to minister to families who lack access to wealth and privilege. I’m more keenly motivated now to develop multicultural programs like Healthy Relationships Seminars.

It’s unfair to expect my friend to share the insights we earned at Fools Mission from hundreds of formative experiences accompanying undocumented immigrants through their valiant, failure-prone quests for County services. It’s nearly impossible to explain in words how the daily lived experience of institutional racism and blind prejudice leads our companions to tell us that the agencies aren’t helping them. I can’t plant their hidden transcripts into his brain, or string the right words in the perfect order to express why we take a different approach. Some things are best learned by direct, first-hand experience. We are free to continue building community instead of caseloads.

Maybe it’s enough to acknowledge that my friend’s ministry might be helpful to his clients in ways I don’t fully appreciate or understand. Perhaps he can suspend his harsh judgments long enough to provide a listening ear to clients that he isn’t ready to extend to me, or to our companions at Fools Mission . I can admit that his motivations probably include sincerity and good will without being drawn into his stories about himself and the world. Even a fool can be a boundary crosser and maintain healthy boundaries at the same time. As the sage once said: “Many are called—few chosen.”